MIDI WORLD – VIDEO GAME THEMES

TIME BREAKDOWN – MIDI Unified

// BPM – it’s a beats per minute 60 000 000/MPQN // PPQN – Pulses per quater note, resolution found in MIDI file // MPQN – microseconds per quaternote or quaternote duration, range is 0-8355711 microseconds (according to MIDI file specification) // QLS – seconds per quaternote (MPQN/1000000) // TDPS – seconds per tick (QLS/PPQN) // TPS - ticks per second (1000000/QLS/PPQN) = (1000000/1/MPQN/1000000/PPQN)

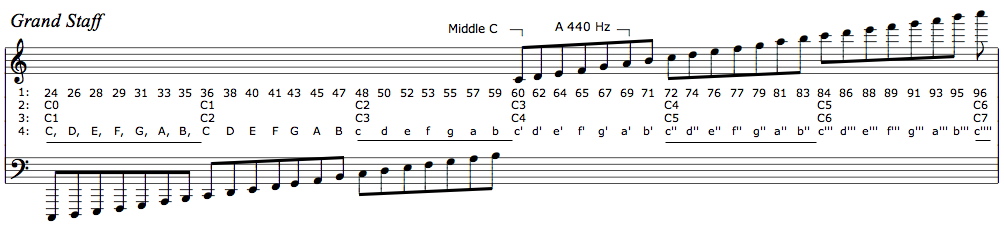

MIDI Note Instrument 35 Acoustic Bass Drum 36 (C2) Bass Drum 1 37 Side Stick 38 Acoustic Snare 39 Hand Clap 40 Electric Snare 41 Low Floor Tom 42 Closed Hi-Hat 43 High Floor Tom 44 Pedal Hi-Hat 45 Low Tom 46 Open Hi-Hat 47 Low-Mid Tom 48 (C3) Hi Mid Tom 49 Crash Cymbal 1 50 High Tom 51 Ride Cymbal 1 52 Chinese Cymbal 53 Ride Bell 54 Tambourine 55 Splash Cymbal 56 Cowbell 57 Crash Cymbal 2 58 Vibraslap 59 Ride Cymbal 2 60 (C4) High Bongo 61 Low Bongo 62 Mute High Conga 63 Open High Conga 64 Low Conga 65 High Timbale 66 Low Timbale 67 High Agogo 68 Low Agogo 69 Cabasa 70 Maracas 71 Short Whistle 72 (C5) Long Whistle 73 Short Guiro 74 Long Guiro 75 Claves 76 High Wood Block 77 Low Wood Block 78 Mute Cuica 79 Open Cuica 80 Mute Triangle 81 Open Triangle

public partial class MidiEvents {

public delegate void MidiRawMessageHandler(int aCommand, int aData1, int aData2);

public delegate void NoteEventHandler(int aMidiId, int aValue, int aChannel);

public delegate void PedalEventHandler(PedalEnum aPedal, int aValue, int aChannel);

public delegate void ControllerEventHandler(ControllerEnum aControllerCommand, int aValue, int aChannel);

public event MidiRawMessageHandler MidiRawMessageEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler NoteOnEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler NoteOffEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler NoteAfterTouchEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler ProgramChangedEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler ChannelAfterTouchEvent;

public event NoteEventHandler PitchBendEnvet;

public event PedalEventHandler PedalOnEvent;

public event PedalEventHandler PedalOffEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler AllNotesOffEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler MainVolumeEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler PanEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler ModulationEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler ResetControllersEvent;

public event ControllerEventHandler ControllerEvent;

The Basic Delegate

An interesting and useful property of a delegate is that it does not know or care about the class of the object that it references. Any object will do; all that matters is that the method’s argument types and return type match the delegate’s. This makes delegates perfectly suited for “anonymous” invocation.

The signature of a single cast delegate is shown below:

delegate result-type identifier ([parameters]);

where:

result-type: The result type, which matches the return type of the function.

identifier: The delegate name.

parameters: The Parameters, that the function takes.

Examples:

public delegate void SimpleDelegate ()

This declaration defines a delegate named SimpleDelegate, which will encapsulate any method that takes

no parameters and returns no value.

public delegate int ButtonClickHandler (object obj1, object obj2)

This declaration defines a delegate named ButtonClickHandler, which will encapsulate any method that takes

two objects as parameters and returns an int.

A delegate will allow us to specify what the function we’ll be calling looks like without having to specify which function to call. The declaration for a delegate looks just like the declaration for a function, except that in this case, we’re declaring the signature of functions that this delegate can reference.

There are three steps in defining and using delegates:

- Declaration

- Instantiation

- Invocation

A very basic example (SimpleDelegate1.cs):

using System;

namespace Akadia.BasicDelegate

{

// Declaration

public delegate void SimpleDelegate();

class TestDelegate

{

public static void MyFunc()

{

Console.WriteLine("I was called by delegate ...");

}

public static void Main()

{

// Instantiation

SimpleDelegate simpleDelegate = new SimpleDelegate(MyFunc);

// Invocation

simpleDelegate();

}

}

}

Compile and test:

# csc SimpleDelegate1.cs # SimpleDelegate1.exe I was called by delegate ...

Calling Static Functions

For our next, more advanced example (SimpleDelegate2.cs), declares a delegate that takes a single string parameter and has no return type:

using System;

namespace Akadia.SimpleDelegate

{

// Delegate Specification

public class MyClass

{

// Declare a delegate that takes a single string parameter

// and has no return type.

public delegate void LogHandler(string message);

// The use of the delegate is just like calling a function directly,

// though we need to add a check to see if the delegate is null

// (that is, not pointing to a function) before calling the function.

public void Process(LogHandler logHandler)

{

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler("Process() begin");

}

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler ("Process() end");

}

}

}

// Test Application to use the defined Delegate

public class TestApplication

{

// Static Function: To which is used in the Delegate. To call the Process()

// function, we need to declare a logging function: Logger() that matches

// the signature of the delegate.

static void Logger(string s)

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

// Crate an instance of the delegate, pointing to the logging function.

// This delegate will then be passed to the Process() function.

MyClass.LogHandler myLogger = new MyClass.LogHandler(Logger);

myClass.Process(myLogger);

}

}

}

Compile and test:

# csc SimpleDelegate2.cs # SimpleDelegate2.exe Process() begin Process() end

Calling Member Functions

In the simple example above, the Logger( ) function merely writes the string out. A different function might want to log the information to a file, but to do this, the function needs to know what file to write the information to (SimpleDelegate3.cs)

using System;

using System.IO;

namespace Akadia.SimpleDelegate

{

// Delegate Specification

public class MyClass

{

// Declare a delegate that takes a single string parameter

// and has no return type.

public delegate void LogHandler(string message);

// The use of the delegate is just like calling a function directly,

// though we need to add a check to see if the delegate is null

// (that is, not pointing to a function) before calling the function.

public void Process(LogHandler logHandler)

{

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler("Process() begin");

}

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler ("Process() end");

}

}

}

// The FileLogger class merely encapsulates the file I/O

public class FileLogger

{

FileStream fileStream;

StreamWriter streamWriter;

// Constructor

public FileLogger(string filename)

{

fileStream = new FileStream(filename, FileMode.Create);

streamWriter = new StreamWriter(fileStream);

}

// Member Function which is used in the Delegate

public void Logger(string s)

{

streamWriter.WriteLine(s);

}

public void Close()

{

streamWriter.Close();

fileStream.Close();

}

}

// Main() is modified so that the delegate points to the Logger()

// function on the fl instance of a FileLogger. When this delegate

// is invoked from Process(), the member function is called and

// the string is logged to the appropriate file.

public class TestApplication

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

FileLogger fl = new FileLogger("process.log");

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

// Crate an instance of the delegate, pointing to the Logger()

// function on the fl instance of a FileLogger.

MyClass.LogHandler myLogger = new MyClass.LogHandler(fl.Logger);

myClass.Process(myLogger);

fl.Close();

}

}

}

The cool part here is that we didn’t have to change the Process() function; the code to all the delegate is the same regardless of whether it refers to a static or member function.

Compile an test:

# csc SimpleDelegate3.cs # SimpleDelegate3.exe # cat process.log Process() begin Process() end

Multicasting

Being able to point to member functions is nice, but there are more tricks you can do with delegates. In C#, delegates are multicast, which means that they can point to more than one function at a time (that is, they’re based off the System.MulticastDelegate type). A multicast delegate maintains a list of functions that will all be called when the delegate is invoked. We can add back in the logging function from the first example, and call both delegates. Here’s what the code looks like:

using System;

using System.IO;

namespace Akadia.SimpleDelegate

{

// Delegate Specification

public class MyClass

{

// Declare a delegate that takes a single string parameter

// and has no return type.

public delegate void LogHandler(string message);

// The use of the delegate is just like calling a function directly,

// though we need to add a check to see if the delegate is null

// (that is, not pointing to a function) before calling the function.

public void Process(LogHandler logHandler)

{

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler("Process() begin");

}

if (logHandler != null)

{

logHandler ("Process() end");

}

}

}

// The FileLogger class merely encapsulates the file I/O

public class FileLogger

{

FileStream fileStream;

StreamWriter streamWriter;

// Constructor

public FileLogger(string filename)

{

fileStream = new FileStream(filename, FileMode.Create);

streamWriter = new StreamWriter(fileStream);

}

// Member Function which is used in the Delegate

public void Logger(string s)

{

streamWriter.WriteLine(s);

}

public void Close()

{

streamWriter.Close();

fileStream.Close();

}

}

// Test Application which calls both Delegates

public class TestApplication

{

// Static Function which is used in the Delegate

static void Logger(string s)

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

FileLogger fl = new FileLogger("process.log");

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

// Crate an instance of the delegates, pointing to the static

// Logger() function defined in the TestApplication class and

// then to member function on the fl instance of a FileLogger.

MyClass.LogHandler myLogger = null;

myLogger += new MyClass.LogHandler(Logger);

myLogger += new MyClass.LogHandler(fl.Logger);

myClass.Process(myLogger);

fl.Close();

}

}

}

Compile and test:

# csc SimpleDelegate4.cs # SimpleDelegate4.exe Process() begin Process() end # cat process.log Process() begin Process() end

Events

The Event model in C# finds its roots in the event programming model that is popular in asynchronous programming. The basic foundation behind this programming model is the idea of “publisher and subscribers.” In this model, you have publishers who will do some logic and publish an “event.” Publishers will then send out their event only to subscribers who have subscribed to receive the specific event.

In C#, any object can publish a set of events to which other applications can subscribe. When the publishing class raises an event, all the subscribed applications are notified. The following figure shows this mechanism.

Conventions

The following important conventions are used with events:

Event Handlers in the .NET Framework return void and take two parameters.

The first paramter is the source of the event; that is the publishing object.

The second parameter is an object derived from EventArgs.

Events are properties of the class publishing the event.

The keyword event controls how the event property is accessed by the subscribing classes.

Simple Event

Let’s modify our logging example from above to use an event rather than a delegate:

using System;

using System.IO;

namespace Akadia.SimpleEvent

{

/* ========= Publisher of the Event ============== */

public class MyClass

{

// Define a delegate named LogHandler, which will encapsulate

// any method that takes a string as the parameter and returns no value

public delegate void LogHandler(string message);

// Define an Event based on the above Delegate

public event LogHandler Log;

// Instead of having the Process() function take a delegate

// as a parameter, we've declared a Log event. Call the Event,

// using the OnXXXX Method, where XXXX is the name of the Event.

public void Process()

{

OnLog("Process() begin");

OnLog("Process() end");

}

// By Default, create an OnXXXX Method, to call the Event

protected void OnLog(string message)

{

if (Log != null)

{

Log(message);

}

}

}

// The FileLogger class merely encapsulates the file I/O

public class FileLogger

{

FileStream fileStream;

StreamWriter streamWriter;

// Constructor

public FileLogger(string filename)

{

fileStream = new FileStream(filename, FileMode.Create);

streamWriter = new StreamWriter(fileStream);

}

// Member Function which is used in the Delegate

public void Logger(string s)

{

streamWriter.WriteLine(s);

}

public void Close()

{

streamWriter.Close();

fileStream.Close();

}

}

/* ========= Subscriber of the Event ============== */

// It's now easier and cleaner to merely add instances

// of the delegate to the event, instead of having to

// manage things ourselves

public class TestApplication

{

static void Logger(string s)

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

FileLogger fl = new FileLogger("process.log");

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

// Subscribe the Functions Logger and fl.Logger

myClass.Log += new MyClass.LogHandler(Logger);

myClass.Log += new MyClass.LogHandler(fl.Logger);

// The Event will now be triggered in the Process() Method

myClass.Process();

fl.Close();

}

}

}

Compile and Test:

# csc SimpleEvent.cs # SimpleEvent.exe Process() begin Process() end # cat process.log Process() begin Process() end

The Second Change Event Example

Suppose you want to create a Clock class that uses events to notify potential subscribers whenever the local time changes value by one second. Here is the complete, documented example:

using System;

using System.Threading;

namespace SecondChangeEvent

{

/* ======================= Event Publisher =============================== */

// Our subject -- it is this class that other classes

// will observe. This class publishes one event:

// SecondChange. The observers subscribe to that event.

public class Clock

{

// Private Fields holding the hour, minute and second

private int _hour;

private int _minute;

private int _second;

// The delegate named SecondChangeHandler, which will encapsulate

// any method that takes a clock object and a TimeInfoEventArgs

// object as the parameter and returns no value. It's the

// delegate the subscribers must implement.

public delegate void SecondChangeHandler (

object clock,

TimeInfoEventArgs timeInformation

);

// The event we publish

public event SecondChangeHandler SecondChange;

// The method which fires the Event

protected void OnSecondChange(

object clock,

TimeInfoEventArgs timeInformation

)

{

// Check if there are any Subscribers

if (SecondChange != null)

{

// Call the Event

SecondChange(clock,timeInformation);

}

}

// Set the clock running, it will raise an

// event for each new second

public void Run()

{

for(;;)

{

// Sleep 1 Second

Thread.Sleep(1000);

// Get the current time

System.DateTime dt = System.DateTime.Now;

// If the second has changed

// notify the subscribers

if (dt.Second != _second)

{

// Create the TimeInfoEventArgs object

// to pass to the subscribers

TimeInfoEventArgs timeInformation =

new TimeInfoEventArgs(

dt.Hour,dt.Minute,dt.Second);

// If anyone has subscribed, notify them

OnSecondChange (this,timeInformation);

}

// update the state

_second = dt.Second;

_minute = dt.Minute;

_hour = dt.Hour;

}

}

}

// The class to hold the information about the event

// in this case it will hold only information

// available in the clock class, but could hold

// additional state information

public class TimeInfoEventArgs : EventArgs

{

public TimeInfoEventArgs(int hour, int minute, int second)

{

this.hour = hour;

this.minute = minute;

this.second = second;

}

public readonly int hour;

public readonly int minute;

public readonly int second;

}

/* ======================= Event Subscribers =============================== */

// An observer. DisplayClock subscribes to the

// clock's events. The job of DisplayClock is

// to display the current time

public class DisplayClock

{

// Given a clock, subscribe to

// its SecondChangeHandler event

public void Subscribe(Clock theClock)

{

theClock.SecondChange +=

new Clock.SecondChangeHandler(TimeHasChanged);

}

// The method that implements the

// delegated functionality

public void TimeHasChanged(

object theClock, TimeInfoEventArgs ti)

{

Console.WriteLine("Current Time: {0}:{1}:{2}",

ti.hour.ToString(),

ti.minute.ToString(),

ti.second.ToString());

}

}

// A second subscriber whose job is to write to a file

public class LogClock

{

public void Subscribe(Clock theClock)

{

theClock.SecondChange +=

new Clock.SecondChangeHandler(WriteLogEntry);

}

// This method should write to a file

// we write to the console to see the effect

// this object keeps no state

public void WriteLogEntry(

object theClock, TimeInfoEventArgs ti)

{

Console.WriteLine("Logging to file: {0}:{1}:{2}",

ti.hour.ToString(),

ti.minute.ToString(),

ti.second.ToString());

}

}

/* ======================= Test Application =============================== */

// Test Application which implements the

// Clock Notifier - Subscriber Sample

public class Test

{

public static void Main()

{

// Create a new clock

Clock theClock = new Clock();

// Create the display and tell it to

// subscribe to the clock just created

DisplayClock dc = new DisplayClock();

dc.Subscribe(theClock);

// Create a Log object and tell it

// to subscribe to the clock

LogClock lc = new LogClock();

lc.Subscribe(theClock);

// Get the clock started

theClock.Run();

}

}

}

Conclusion

The Clock class from the last sample could simply print the time rather than raising an event, so why bother with the introduction of using delegates? The advantage of the publish / subscribe idiom is that any number of classes can be notified when an event is raised. The subscribing classes do not need to know how the Clock works, and the Clock does not need to know what they are going to do in response to the event. Similarly a button can publish an Onclick event, and any number of unrelated objects can subscribe to that event, receiving notification when the button is clicked.

The publisher and the subscribers are decoupled by the delegate. This is highly desirable as it makes for more flexible and robust code. The clock can change how it detects time without breaking any of the subscribing classes. The subscribing classes can change how they respond to time changes without breaking the Clock. The two classes spin independently of one another, which makes for code that is easier to maintain.